Archive Highlights

From the Archive: Poor Lady Strickland

It is an enduring image of the nineteenth century novel – the ‘mad’ wife cruelly isolated and supplanted in her husband’s affections by another member of his household. It is the plot of Jane Eyre but also has resonances in the fiction of Wilkie Collins and the real life stories of Mrs Dickens, Mrs Thackeray and Lady Bulwer Lytton. Women (‘mad’ or otherwise) were powerless to contest such treatment; they did not even have rights over their own children before the 1839 Infant Custody Act and any property they brought to the marriage, or earned in the course of it, was legally owned by their husbands.

The tragic story that emerges from the Archive begins not with a document but with the box in which some are stored.

Inside the wooden lid we read:

This box was made for

LUCY by Papa.

Jany 3rd 1830

Lucy was Lucy Henrietta Strickland, who was born in 1822 and who came to Cotesbach Hall in 1844 when she married the Reverend James Powell Marriott. ‘Papa’ was Sir George Strickland, 7th Baronet and Member of Parliament. The wooden box was doubtless an adoring father’s heartfelt gift – but Sir George had taken away so much more. When Lucy was only six years old (and her brothers aged nine, eight and seven), Sir George declared his wife Mary insane and forbade her any further contact with her children. To quote the on-line ‘History of Parliament’:

“Matters came to a head in 1828 when his wife, who had been suffering ‘strange nervous attacks since she was a girl’, became delirious and plunged her hand into the fire, seriously burning herself. Strickland packed her off to Constable [her father, the owner of Wassand Hall] to convalesce and determined that she should never again be left alone with any of their children until she was cured, nor would he live with her until then. They were estranged for the next 37 years.”

This was, in fact, the rest of Mary’s life. She died in January 1865 after more than half a lifetime of separation from her husband. She was not confined, as so many women were, to an asylum or to the proverbial attic; in some ways, her fate was more lonely, for she lived in large family properties teeming with servants but with little companionship. She was free to travel to various spa towns and seaside resorts but did so generally accompanied by her elderly clergyman father. She was even able to see her children as adults – but had forever lost their precious childhood years. All four were sent away to school; Mary’s father was willing to foot the bill as long as they were allowed to spend the holidays with him at Wassand Hall, but Sir George refused even though money was becoming a problem. Sir George sued the Reverend Constable for not fulfilling the arrangements to pay Mary’s dowry: the Reverend Constable prosecuted Sir George to recover some of the dowry that had been paid in recognition of his expenses in taking Mary back into his own household. Family relationships were fragmented beyond repair.

Sir George, meanwhile, had moved to London. He had become M.P. for Yorkshire (at the time, a single vast constituency) in 1830 and rented a ‘capital residence of modern erection’ in Spring Gardens, Westminster, overlooking Trafalgar Square. The 1841 census finds him alone in his grand house save for Jane Leavens, a young female servant. Later that year, Jane gave birth to a son Harry Leavens, the first of three children she would bear to Sir George. By 1851, Sir George has moved to a larger house in Piccadilly accompanied by Jane and the three Leavens children; all are marked as ‘visitors’ (although the household tellingly also contains a governess) and Jane has been elevated in status to ‘proprietor of land and houses’. The charade continues in the next census; Sir George is at one of many family properties, Walcot Hall in Lincolnshire (called by the census enumerator ‘The Mansion’), and is still accompanied by Jane and the three children, who have now been joined by Jane’s orphaned niece Sarah. Jane is ‘housekeeper’ but all four children are now Sir George’s ‘adopted’ sons and daughters. By the time of the 1871 census, the abandoned wife Mary had died leaving Sir George free to marry again, which he did aged 84 in 1867; a previously ‘adopted son’ is acknowledged in the census and shares Sir George’s surname, and Jane (the daughter of a Yorkshire saddle-maker) has taken her place as Lady Jane, chatelaine of the imposing Howsham Hall and mistress of 13 servants.

Photo acknowledgement: Aynhoe Park, CC BY-SA 4.0

<https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

Lady Jane outlived Sir George by more than twenty years and died in October 1898 possessed of £96,000.

The Strange Story of the Architect’s Wife

Archive documents always have a story of some sort to tell but this one could narrate a whole Victorian novel!

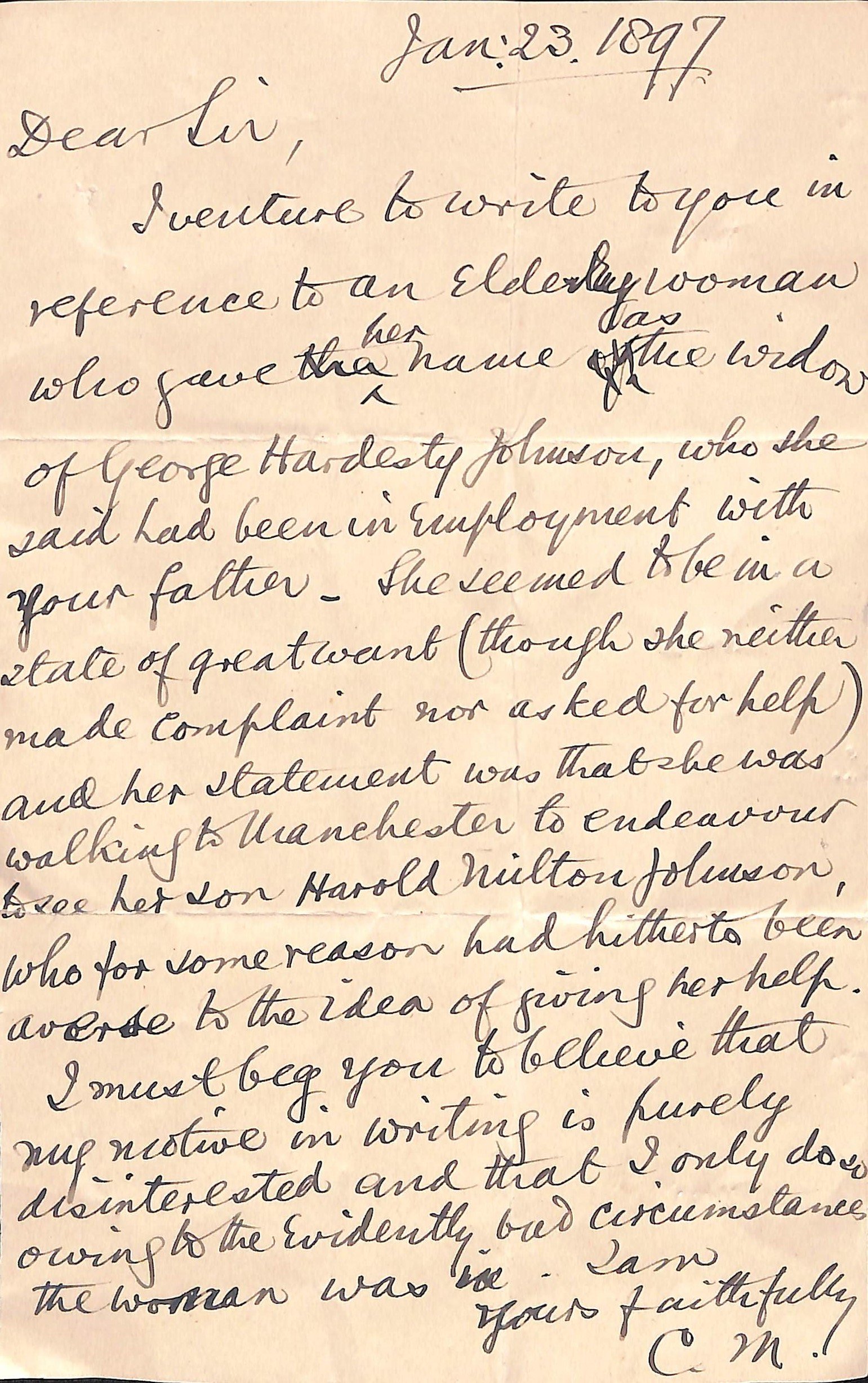

The tale begins with document .3250, the draft of a mysterious letter dated 23rd January 1897. Charles Marriott, head of the Cotesbach Hall family, is writing to an unnamed recipient requesting help for an elderly woman “in evidently bad circumstances”. “She gave her name as the widow of George Hardesty Johnson, who she said had been in employment with your father. She seemed to be in a state of great want (though she neither made complaint nor asked for help) and her statement was that she was walking to Manchester to endeavour to see her son, Harold Milton Johnson who for some reason had hitherto been averse to the idea of giving her help.”

Such a short text raises so many intriguing questions. Where and how had Charles Marriott come across the woman? If in Cotesbach, why was she setting out to walk a journey of 130 miles? Why was her son reluctant to come to her aid? Who was to receive the letter and how was he likely to be able to help? Surely, the unusual names contained in the letter would be easy to research and would reveal some answers.

Research, in fact, only deepened the mystery. George Hardesty Johnson, it transpired, was a famous nineteenth century architect and civil engineer who did ground-breaking work in the fireproofing of buildings. He specialised in facades made of cast iron and some of his structures still survive – in the United States. Harold Milton Johnson, who was indeed George’s son, had been born in New York in 1865. There were references to Manchester, however, and the “History of Chicago” (published in 1886) gave a brief biography of George Hardesty Johnson, “one of the most prominent architects of the age”; he was born in Manchester in 1830 and was apprenticed there for three years to the contractor and builder Robert Neill. He emigrated in 1852, “accompanied by his wife and child”, and took up a position as manager of Daniel Badger’s Architectural Ironworks in New York. The 1865 New York census finds the family (now with 5 children - but not yet Harold - and an Irish maid) living in Richmond, Staten Island.

The name listed on that census for George’s wife was Maria S. Johnson. A little more research revealed that George had lied to his biographers about the date of their marriage. The couple had met in Manchester where Maria Salkeld had been working in her sister’s pub, and they had had a son (George Edward) in 1853, but they did not marry until 1856 in Manhattan. Maria, it appeared, must have died about ten years later; she gave birth to her sixth and last child (Harold Milton) soon after the census in 1865 but by the end of December 1869 George had returned to Manchester and married a second wife (Emily or Emmeline) Johnson in the Cathedral there. Emily was listed as a spinster and George a widower. Their marriage was announced in the Manchester newspapers.

The elderly woman who was the subject of our letter must, then, have been Emily Johnson, not the biological mother of Harold Milton but his step-mother. She went back to the USA with George in January 1870 and gave birth to two sons in Manhattan, but returned with the boys to her family in Porter Street, Sheffield when George himself died in 1879. The censuses of 1881 and 1891 find her at the same address, so this places her, at least, in the right country to have met Charles Marriott in 1897 – except for the fact that she died (still in Porter Street, according to her burial record) on the 6th of March 1895. The mystery deepens.

All is made clear (or as clear as it is likely to become) by an entry in the 1871 census of Manchester. A Mrs Mary Mills and her daughter Deborah have a “visitor” staying with them at an address in Brierley Avenue, Ardwick. She is Maria S. Johnson born in Manchester and living on an “allowance from husband”. She is a “lunatic”.

It is at this point that the plot becomes truly worthy of a Victorian novel. George Hardesty Johnson, the celebrated and wealthy architect, has brought the mentally ill Maria (mother of his six children) back to Manchester where she cannot disgrace him, lodged her with strangers and returned to the USA with a new wife married openly but bigamously.

Maria subsequently disappears from the records until Charles Marriott writes about her in January 1897. Where has she been for the intervening 26 years? The most likely scenario is that she has spent time in an asylum. When her husband (he was legally still her husband) died and his financial support dried up, whoever was looking after her would probably have had little alternative but to commit her to an institution. There were literally hundreds of asylums in Victorian England and patients in them were usually recorded only by their initials in census returns, so we are unlikely to have a definitive sighting of Maria if this was her fate. It might help, however, if we knew where to look for her. So where could her path and that of Charles Marriott have crossed?

Another Archive document (.2041, the diary of Charles’s daughter Eve) gives us some clues here. Eve reports on Thursday 21st January 1897: “Mother & Father stayed at Lowick”. Lowick is a village in Northamptonshire and it is where their old friends the Watsons (John Sikes Watson, former vicar of Cotesbach, and his family) lived. Staying overnight was a necessity because, even in ideal conditions, the journey of about 35 miles cross-country would have been an arduous one in a carriage – and conditions were far from ideal that January. Eve remarks that the weather was exceptionally icy, with night-time temperatures of 18F (nearly -8C) and “The country white with snow, which was drifting hard”. As the carriage bearing Charles and his wife Emily battled through the lanes westward to Cotesbach, or took the slightly longer but probably clearer route through Northampton, the Marriotts must have sighted Maria Johnson alongside the road. Her ‘bad circumstances’ were doubtless evident from her clothing, inadequate for the extreme conditions, and we can imagine that she would have been offered a lift for a small part of her long journey, telling her story on the way.

It would be interesting to know how Maria explained her presence in the Midlands. She cannot have walked far in such dreadful weather so must surely have set out from somewhere near the Leicestershire/Northamptonshire border, but we have no way of knowing what she was doing there. It may not be coincidence that Northampton was home to two very large lunatic asylums, St Crispin’s and St Andrew’s.

At some point, Maria must have been set down to resume her walk while the Marriott coach continued to Cotesbach. The next day, Charles Marriott fulfilled his promise to write to Robert Neill of ‘Midfield’, Northumberland Street, Manchester (doubtless finding the address in the same way as I did, from a street directory) about Maria Salkeld Johnson’s sad plight. That is the last occasion on which we can find her definitely mentioned in historical records.

Did she reach Manchester? We cannot know. Did she find her son Harold? Almost certainly not; he had (like his father) completed an apprenticeship with Robert Neill & Sons in Manchester but had arrived back in the United States on a ship called the ‘Etruria’ on 17th December 1888. She might conceivably have made contact with her only surviving daughter, Maria Clara Helena, who was born and brought up in the United States but who married a German called William Schroeder in Manchester in 1892 and lived there with her husband, a son and a daughter until at least 1911 before returning to the United States where she died in Tennessee in 1941. Did Maria Johnson even know that her daughter was in England?

So there we have the Victorian plot worthy of Mrs Gaskell or the Brontës, with riches gained and lost, children lost and (possibly) found, a lying, treacherous husband with a social status to protect, and a wife dubbed insane and shuffled out of sight. As in a much more modern kind of novel, however, we are left to choose our own ending. The name ‘Maria Johnson’ is common enough in the records for various possibilities to exist and for certainty to be impossible. These are the likely scenarios:

There is a Maria Johnson of about the right age buried in the Southern Cemetery in Manchester, very close to where Maria’s daughter was living. The grave has no headstone but we know from the cemetery register that it dates from the summer of 1899. Was Maria taken in by her daughter and cared for, surrounded by her family, until then?

There is also a record for a Maria S. Johnson returning to New York from the UK by ship in 1897. Did she find a benefactor in Mr Neill of Manchester (a very wealthy businessman, former Mayor of Manchester and a Justice of the Peace, so well placed to give assistance) and did he help her to get to the United States in a continued search for her son Harold? If so, is she the Maria S. Johnson who died aged 68 in New York on the 3rd of October 1899?

Or was Maria simply returned to the obscurity of an asylum for her remaining years, the odd little letter in the Archive her only memorial?

From the Archive: Death and the springtime garden

In January 1868, a child at Cotesbach looks forward to the plants and flowers that the changing seasons will bring and imagines a conversation between gardeners. Idyllic – except that the scene is an allegory and one whose significance was so soon to overshadow the family.

The text of document .2165.1 looks like a carefully executed child’s handwriting exercise but its theme, with uprooted plants and cut flowers, is untimely death. This, of course, was a fact of life in mid-nineteenth century families and children could not be protected from the early loss of siblings. In Lutterworth, an area well outside the overcrowding and deprivation of growing Victorian cities, more than 12% of infants did not even reach their first birthday; in Manchester in the 1860s, the figure was nearly 21%. The Marriott family of Cotesbach Hall were more affluent than most but were not immune; there was a dead baby in 1866 and the loss of 7-year-old Frederick from diphtheria in 1858.

The most resonant early death of all happened only a few months after our document was written and is doubtless why the little text was kept. Robin Marriott, the oldest son of his generation and therefore the heir to the Cotesbach estate, had just attained his majority and was studying at Oxford when a dreadful accident befell him. During an attempt to climb from his window to that of a friend in a neighbouring second floor room, Robin fell thirty feet to the stone flags of the quadrangle. His parents were informed by telegram and set out with all haste but their quest was hopeless; as their own telegram from Oxford to Cotesbach (preserved in the Archive in draft form) reports, “We are too late. Robin fell while climbing. He never spoke after. Said to have suffered no pain.”

A promising flower had been gathered far too early by ‘the Master’ and the course of Cotesbach history shifted on its axis.

From the Archive: The Tichborne Claimant

In a small, leather-bound notebook dating from the early 1870s [doc no .3102] we come across an unusual Archive find – a joke.

Riddle: Why is Kenealy like the Claimant?

Because they are both famous for Wapping relations.

As we all know, a joke that has to be explained is no joke at all; a closer examination of this one, however, reveals an interesting piece of history.

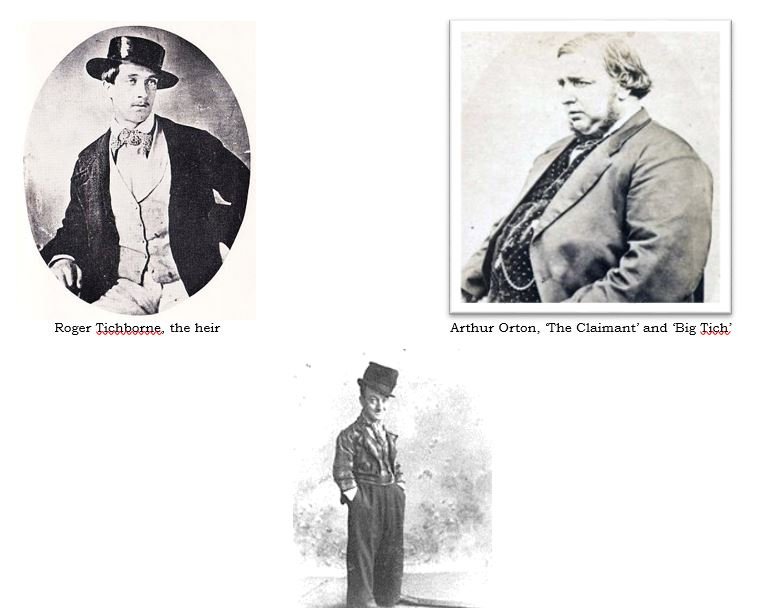

The ‘Claimant’ was the Tichborne Claimant whose story was a sensation in the British press for years, whose court case was one of the longest in the annals of the justice system and whose stage career left its mark on the English language.

The tale begins in 1854 when Roger Tichborne, the heir to an English baronetcy and a considerable fortune, was lost at sea somewhere between Rio de Janeiro and Jamaica. The wreckage of his ship was found but not a single survivor, although there were rumours that some of the passengers had been rescued by a passing vessel and taken to Australia. Roger’s mother clung to that hope and advertised in Australian newspapers for reports of possible sightings of her tall, willowy and slightly effeminate son. In 1865 (when Lady Tichborne had added to her advertisements the fact that her husband had now died, leaving Roger the extensive family estate in Hampshire), an Australian immigrant living in Wagga Wagga came forward to claim his inheritance.

Members of the Tichborne family and staff were unconvinced by the burly and semi-literate ‘Claimant’ who spoke with a marked Cockney accent but Lady Tichborne was completely taken in. She championed him until her death in 1868 but then he was forced to do battle with the less gullible members of the family through the courts. To cut a very long story short, the Claimant was eventually exposed as one Arthur Orton, a butcher whose family still lived in Wapping, and was sentenced to fourteen years’ imprisonment. His eccentric defending counsel, Edward Kenealy, was reproved for his scurrilous and mendacious conduct during the trial.

Orton continued to maintain his innocence and, for some years after his conviction, enjoyed a degree of support amongst the British populace. This had dwindled to almost nothing, however, by the time he was released from prison in 1884 to a life of destitution and eventual obscurity. For a few years he scraped a living by performing as ‘Big Tich’ in circuses and music halls; in reference, no doubt, to the stark contrasts between the Claimant and the real Roger Tichborne, an existing music-hall artist called Harry Relph (who was just 1.37 metres tall) adopted the stage name ‘Little Tich’, thus giving the English language the expression ‘titchy’.

This is almost the only trace now of a Victorian sensation – a word in the dictionary…and, of course, a joke in an old notebook.

Riddle: Why is Kenealy like the Claimant?

Because they are both famous for Wapping relations.

Orton was exposed as having family roots in Wapping; Kenealy was censured for the ‘whopping’ tall stories he told in Orton’s defence. Get it now? Oh, well ….

From the Archive: a Victorian Obsession

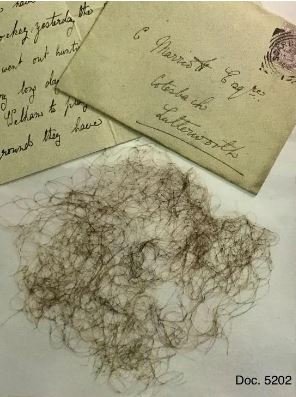

Curiously, several Archive documents contain locks of hair. Here is an example from 1844, sent from Tasmania to Cotesbach with news of a birth; a lock of the baby’s hair is carefully sewn to the page.

Queen Victoria’s mourning brooch

containing a lock of Albert’s hair.

In Victorian times hair was almost an obsession, snipped from both living and dead and kept in lockets, in frames or woven into jewellery. In an era before photographs were easily available, hair became a tangible and intimate connection between people, a treasured keepsake when loved ones were far away or ‘gone before’.

The Victorians were not the first to revere hair in this way, of course. After the execution of Charles the First in 1649, his supporters cherished locks of his hair which were often worn beneath clothing in a closed and secret locket. It was the Victorians, however, who made the cult public; in 1854 Wilkie Collins wrote that hair jewellery was, “in England, one of the commonest ornaments of women’s wear.” When Prince Albert died in 1861, Queen Victoria had eight pieces of mourning jewellery created using locks of his hair and was never without at least one of them for the remaining forty years of her life.

…None of which explains why an archived letter of 1900 contains a hairnet!

Letter of 1900 containing a hairnet.

From the Archive: An “Arctic fairy land”

A letter sent from Cotesbach on the 5th February 1917 contains a magical description of some wintry weather:

“Seven inches of snow fell, and as there was scarcely any wind, there has been a wonderful bit of scenery all today, and now in the bright moonlight. For the shrubs and trees are laden with very thick but very light snow, and it is like a sort of Arctic fairy land. I suppose you have been having skating, and the ice ought to be very strong.”

February 1917 was the coldest month of the winter in the United Kingdom, registering the lowest temperatures for more than twenty years. It ranked as the fifth coldest February of the whole 20th century. The thermometer readings at Cotesbach were by no means exceptional for the Midlands; writer Charles Marriott noted an overnight temperature of 4 degrees Fahrenheit (-15.5 C) on the 5th February and on the same night 2 degrees F (-16.6 C) was recorded in Benson, Oxfordshire. Charles’s son Jem (James Edmund Marriott of the Royal Flying Corps, serving in France) had also reported “28 degrees of frost”, or -15.5 degrees C, and parts of Continental Europe were even colder.*

The effect on soldiers in the trenches of WW1 are beyond imagining. What follows is an account by NCO Clifford Lane, quoted on the website of the Imperial War Museum:

“The coldest winter was 1916-1917. The winter was so cold that I felt like crying.... I’d never felt like it before, not even under shell fire. We were in the Ypres Salient and in the front line, I can remember, we weren’t allowed to have a brazier because it weren’t far away from the enemy and therefore we couldn’t brew up tea. But we used to have tea sent up to us, up the communication trench....It would start off boiling hot; by the time it got to us in the front line, there was ice on the top it was so cold.”

After long weeks of such privations, of exposure and frostbite, a thaw set in – and the notorious, deathly mud returned with a vengeance. It seems a very long way from the “Arctic fairy land”, yet Cotesbach did not remain untouched by the war. The letter is on black-edged paper for two sons already lost.

* The Meteorological Office has an on-line archive with (amongst other fascinating items) historical weather reports, searchable by date:

https://digital.nmla.metoffice.gov.uk/archive